August 10, 2014

Never-give-up Najee

It's tempting to start this article out with some sonorous quotation from an exalted historical figure about tenacity. But that's not needed. Instead, it's better to simply allow A.B. Najee to tell his own inspiring story of perseverance.

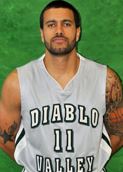

First some recent background: in 25 games (11 starts), this past season as a sophomore guard on the Diablo Valley College (DVC) team, the 6-foot-2 Najee averaged 8.4 points per game, shooting 47%, 33% and 77% respectively. He also posted 3.3 rebounds and 2.4 assists a contest while nightly defending the opponent's best guard.

This production earned him a full scholarship to Mayville State in North Dakota, a school that competes athletically at the NAIA level.

He will play basketball for a four-year school, his higher education will be paid for and he will graduate with a degree in communications - journalism.

Yet none of that seemed possible, let alone probable, just a few years ago. For this was a young man who never played high school basketball.

“I tried out in high school (Berkeley High). As a freshman and a sophomore, I was cut. I didn't try my junior year. As a senior, I made the final cut but then I was told I would never play.”

It made no sense to continue. “Every one said I wasn't good enough,” Najee recalled.

Thus ended his formal prep hoops involvement.

A year went by and then Najee tried out for the Contra Costa College squad. He was cut.

Later came an attempt to make the College of Alameda team. It was no thanks again.

By now if not much sooner, most people would have gotten the message the basketball gods and goddesses were sending him. Not Najee. He was repeatedly being told to make other plans, that playing formal basketball wasn't meant to be for him. There was a huge helping of “get over it” being served but Najee refused to bite.

“Me, my brother Khufu (who will be a senior at IUPUI this season), and a friend, Marcus Grimes, grew up playing every day. We dreamed we would make it together and play together. They were able to live the dream and I was the outsider, the person who wouldn't succeed.”

One time a youngster approached Najee with this blistering question: “You're Khufu's brother, why is he so good and you're so bad?”

“From then on, I refused to be bad -- I had to be good.”

“People would tell me I couldn't shoot, so I would work on that. Whatever I was told I couldn't do, I would work on. I kept working. My brother told me not to quit. I didn't want to be the guy who tried but stopped.”

“When I looked in the mirror, I would say ‘I see a basketball player.’ I never let anyone stop me. I never accepted failure. No one starts at the top -- it's who decides to keep climbing the hill that succeeds. You never know when you will accomplish something so what if you quit a day before reaching your goal? I kept saying ‘it's today’ and when it didn't happen, I would say ‘it's tomorrow.’ I wouldn't take no for an answer.”

Life became a focus of shooting and dribbling—“doing drills”—day after day, week after week. Najee's mother and brother stayed united with him as a support system.

His father passed away when Najee was still in high school. After that, “I had a father figure but he never supported me, he never gave me that. He would say I wouldn't make it, that other guys would but not me. He wasn't in my corner.”

When Najee finally made the DVC team, he texted three words to this individual: “I did it.” He received no response.

As a Viking, he got to play against the coaches who deemed him not talented enough.

“I'd see them and say to myself ‘I can't wait.’ When I would score, I would look over at the coach and they would look away. I never heard anything from the doubters.”

“Playing for Coach (Steve) Coccimiglio was definitely beneficial. I learned a lot from him. People kept wondering why I couldn't make any teams, asking whether it was my attitude. When I made the [DVC] team, I could answer ‘if my attitude was a problem, I wouldn't be playing for Coach Coccimiglio. He has a no tolerance policy for troublemakers.’ He used me for examples [when demonstrating for other players], saying ‘A.B. does everything I want him to do and more. That's the guy to follow.’”

Najee recounted Coccimiglio using this analogy in describing his approach: “if A.B. hadn't eaten in two days and was given a bowl of soup and a fork with two prongs missing, he would have the bowl clean in five minutes.”

Najee also gives credit to DVC Assistant Coach Derrick Jones as their paths crossed when the latter was an assistant at Berkeley High, as well as skills trainer Bradley Johnson for his time and effort in improving Najee's game.

The Mayville State coaching staff reached out to Najee in July. “They called me and kept calling. They saw some game film of me and wanted me to sign right away. They were very persistent.”

Another school, a private DII one in New York, also pursued Najee. “While I felt I would be a good addition in New York, Mayville wanted me so much more. I liked the coach and the lifestyle and the environment. I'm a low key guy.”

“Now the plan is to graduate and initially pursue professional basketball. I want to play overseas for two years to say I did it and then call it quits.”

“I got so used to being talked about negatively, it's hard to accept that I'm good. But I found out that if I want to do something in life, it (his journey) prepared me.”